OneCoin Leaks: Hogan Lovells’ second legal opinion (2017)

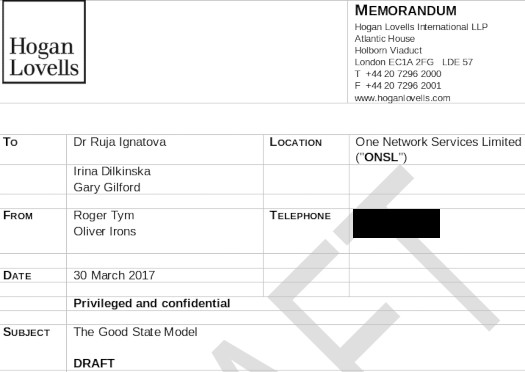

In March 2017 OneCoin commissioned a second legal opinion from the UK law firm Hogan Lovells.

In March 2017 OneCoin commissioned a second legal opinion from the UK law firm Hogan Lovells.

The document we’ve obtained is dated March 30th and was put together by Roger Tym and Oliver Irons.

It is marked “draft” and addressed to Ruja Ignatova, Irina Dilkinska and Gary Gilford, of One Network Services Limited.

OneCoin first approached Hogan Lovells for a legal opinion in 2016. According to background provided by the law firm, Hogan Lovells was to

focus on whether the MLM activities performed by OneLife could be considered to constitute the unfair commercial practice of establishing, operating or promoting a pyramid promotional scheme (the “Pyramid Scheme Prohibition”) as a matter of English law.

We don’t have this document but can report that Hogan Lovells found OneCoin was a pyramid scheme, as per UK law.

As a result, the firm provided OneCoin with “certain areas that required further consideration”.

Note that we can’t verify said recommendations would have done anything to change OneCoin being a recruitment-driven Ponzi scheme, as we haven’t seen the original 2016 document.

Hogan Lovells’ 2017 opinion does not take into consideration OneCoin’s investment opportunity, only the MLM recruitment side of it.

The leaked document came about after OneCoin asked the firm

to prepare a note on the legal and regulatory requirements applicable to MLM activity carried on in the UK as part of the “Good State Model” proposed in our Revised Scope of Work dated 23 January 2017.

The “Good State Model” appears to be Hogan Lovells’ term for recommendations made to OneCoin.

It is comprised of three components of analysis:

- Part I: English law and regulatory requirements applying to MLM businesses;

- Part II: Industry standards; and

- Part III: Good practice.

In Part I of their analysis, Hogan Lovells points out various affiliate behavior that would run foul of the UK’s Unfair Commercial Practices Directive law (UCPD).

This is the usual stuff; misleading action, misleading omissions and commercial practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair.

One could argue pretending OneCoin, as Hogan Lovells put it,

involve(s) the marketing and sale of online educational programmes, known as the OneAcademy Advanced Learning System…

… is misleading in and of itself. That would mean OneCoin was by definition in violation of the UCPD – but that’s not the route Hogan Lovells took.

The law firm advised OneCoin that it was at risk if affiliates marketed the opportunity in violation of the UCPD.

OneLife or one its IMAs will commit an offence under the CPRs: (a) if it engages in a commercial practice that knowingly or recklessly breaches the required level of professional diligence and the practice materially distorts (or is likely to distort) the behaviour of the average consumer1 (the “general prohibition”); or (b) in situations involving the following;

(i) a misleading action;

(ii) a misleading omission;

(iii) an aggressive commercial practice.

(iv) a banned commercial practice listed in Schedule 1 to the CPRs (with minor exceptions)

Again, OneCoin by its very nature was fraudulent (pretending it wasn’t an investment scheme). Hogan Lovells’ legal opinion however conveniently ignores the multi-billion dollar Ponzi component of the company.

Should OneCoin’s affiliates “breach the rules”, Hogan Lovells suggests the following remedies:

(a) Via a private action by a consumer for breach of contract (other than in respect of additional requirements for telephone calls to conclude a distance contract); and

(b) Public enforcement: An enforcement authority must consider any complaint about breach of the CCRs, and may apply for an injunction to secure compliance.

The report emphasis plausible deniability on OneCoin’s behalf, through what Hogan Lovells terms the “due-diligence defense”.

To make use of this defence:

OneLife must prove that the “that the commission of the offence was due to—

(i) the act or default of another, or(ii) reliance on information given by another, and

that OneLife took “all reasonable precautions and exercised all due diligence to avoid the commission of such an offence by OneLife or any person under OneLife’s control.”

A few months after Hogan Lovells provided this document to Ignatova, OneCoin abandoned arrested Indian affiliates.

The justification Ruja Ignatova provided sounds eerily similar to what Hogan Lovells prescribed.

All these peoples [sic], we have removed for compliance from the company.

These people get in trouble, get prosecuted by the authorities. And to be very, very honest, we also cooperate with the authorities on things like this.

We are speaking to the Indian authorities. We have delivered the names of the people who have violated the firm policy.

We have warned everybody in India not to do so and I have even stopped the registration process of India yesterday.

The arrests were the aftermath of Indian authorities declaring OneCoin was a Ponzi scheme and issuing an arrest warrant for Ignatova.

Moving on to part 2, industry standards, Hogan Lovells suggests OneCoin join a “trade organization” – namely the UK’s Direct Selling Association.

While you may decide not to pursue membership of the DSA, it would nevertheless be very helpful for OneLife to review the IMA Agreement, General Terms and Compensation Plan (as defined in the Original Advice) against the DSA Codes as parts of the gap analysis.

Whether or not OneCoin applied to join the UK DSA is unclear.

Part 3 of the report pertains to “good practice” and seems to bizarely reference OneCoin’s non-existent “consumer” retail customers.

One of the key areas for OneLife to evaluate is the process by which its IMAs are on-boarded.

Of particular importance in this regard is the need to be able to identify “consumers” and to prevent them from signing up as IMAs.

As per OneCoin’s business model, there are no consumer retail customers. Everyone is an affiliate, so what Hogan Lovell have based this section of their report on I’m unclear on.

The rest of the section focuses on collecting personal information from OneCoin affiliates.

Where possible, credit checks should be carried out on IMA applicants to provide further background on their current and historic financial position.

This should act as a filter to prevent bankrupt / insolvent and heavily indebted individuals / firms from becoming part of the OneLife network.

Onelife should also put in place appropriate screening procedures to ensure that any individuals who have been suspended or excluded from the OneLife network cannot successfully re-apply / be re-recruited into the network.

Hogan Lovells’ report concludes with a Good State Model annex, which provides recommendations for OneCoin to implement.

1. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition

If IMAs are not “consumers” then the Pyramid Scheme Prohibition of the CPRs will not be breached.

Evidence demonstrating that OneLife manages and monitors the application process to ensure that consumers do not become IMAs (in compliance with the terms of the IMA Agreement and General Terms) in the form of written policies and procedures (with supporting compliance/audit requirements and records) would be very helpful in this regard.

Everyone in OneCoin was an affiliate who invested in Ponzi points. There was no retail offering so this recommendation is meaningless.

2. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: Consideration given by consumer

Where the consideration is relatively low in value and genuinely given in return for access to the information and learning provided in a particular Educational Package and / or to enable the IMA in question to improve their ability to sell such a package to others, it has a much better chance of being viewed as part of a legitimate MLM / direct selling scheme.

We noted the following action:

It would be useful for you to consider the numbers of IMAs who operate as Rookies (i.e. without giving consideration) as against the numbers who purchase each of the various packages in order to get a better understanding of how the business operates here.

We understand that only a small percentage (less than 1%) of OneLife members are on a package of EUR 1,000 or above.

Basically Hogan Lovells are stating OneCoin is less likely to be seen as a pyramid scheme if its victims lose less money individually.

Yeah, that’s as terrible as it sounds.

One important thing revealed in this recommendation though is that Hogan Lovells were aware of OneCoin’s package tiers.

Strangely enough, the fact that no matter how much a OneCoin affiliate invested they received the same education package wasn’t addressed.

3. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: Compensation derived from introductions.

The ability to generate income / earn commission from the introduction of other consumers into a scheme, rather than through the sale or consumption of products, will be a key indicator of whether OneLife’s MLM activities will fall foul of the CPRs as a pyramid promotional scheme.

We noted the following actions:

1. The first paragraph of the Compensation Plan acknowledges that not everyone who chooses to purchase an Educational Package will also choose to be an IMA.

Those who simply make their purchase to access the educational material in the packages in order to learn about finance and the ability to make money by trading on the financial markets are unlikely to be doing so as part of their business and will therefore be “consumers”.

Regardless of what OneCoin’s compensation plan stated, everyone in the company was an affiliate with access to the compensation plan.

Again, OneCoin had no retail customers (consumers as referenced by Hogan Lovells).

This type of sale / referral by IMAs will clearly fall outside the scope of a pyramid promotional scheme because the consumers are not becoming participants in the scheme as IMAs so if OneLife can demonstrate that this kind of sale makes up a significant percentage of the overall referrals by its IMAs, it will provide strong evidence that the MLM activity is focused on the sale of products and not on the need to recruit new participants to the scheme.

“This type of sale” didn’t exist. Which, if Hogan Lovells had done their homework, leads to the conclusion OneCoin is a “pyramid promotional scheme”.

The way in which this part of the Compensation Plan operates is not entirely clear but there is an obvious link established between the building of teams / recruitment of IMAs and the level of earnings that can be achieved which raises a potential issue with regard to whether IMAs primarily derive their compensation from sales or the introduction of others into the scheme.

It would therefore be advisable for ONSL to review this aspect of the plan and re-word / clarify how it operates in practice to make sure that IMAs are able to understand it and prevent it falling into Pyramid Promotional Scheme territory.

You sign up as a OneCoin affiliate, invest and get paid to recruit others who do the same.

There’s no mystery here, either now or back in 2017. And there’s also no way to “prevent” OneCoin’s business model from “falling into Pyramid Promotional Scheme territory”.

IMAs are paid on a weekly basis with 60% of their commission deposited into their cash account which can be transferred onto a card and / or bank account and the remaining 40% into a OneLife currency trading account.

It is not clear from the MLM Agreement what IMAs are permitted to do with the funds in the trading account although it appears that they can make purchases of Educational Packages from it.

These funds are used to reinvest in OneCoin Ponzi points. How was this not followed up on by Hogan Lovells?

Our recommendation with regard to the 60 / 40 split of the income earned by IMAs is essentially that it needs to be documented more clearly in the Compensation Plan and IMA Agreement.

At present, it is not clear exactly what IMAs are able to do with the 40% in their trading account.

Based on Frank’s response to Dr Ruja, it appears that most users purchase more tokens for OneCoin mining but can also use the trading account monies to make purchases (at present including the OneLife tablet and educational packages).

This should be clearly explained in the documentation.

The reason it’s not “explained in the documentation”, or at least the documentation provided to Hogan Lovells, is because it reveals OneCoin is a Ponzi scheme.

Again, instead of turning a blind eye, this is something Hogan Lovells should have pressed on.

Who puts together a legal opinion without fully understanding the subject material?

4. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: Contracts with participants

Pyramid schemes designed to look like legitimate MLM / direct selling arrangements will generally not offer contracts to participants.

OneLife has a contract with participants through the

MLM Agreement that all IMAs are required to sign up to.

According to the IMA Agreement, OneLife has the option to take various corrective measures in the event of IMAs engaging in fraudulent, deceptive or unethical business conduct.

These range from written warnings and requiring IMAs to take remedial action to loss of rights to payments, suspension or termination of the IMA Agreement and the imposition of fines.

The wording in the documentation is only as good as the way in which OneLife operates in practice.

OneLife == OneCoin and OneCoin was a fraudulent Ponzi scheme. The documentation Hogan Lovells is referencing is therefore meaningless.

5. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: No Obligation to invest large sums upfront

Due to the nature of the OneLife scheme which will involve IMAs purchasing potentially very expensive Educational Packages in order to participate at a higher level in the Compensation Plan, this is an area where the MLM scheme operated by OneLife is likely to take on this characteristic of a pyramid promotional scheme.

No argument from me on that.

On the plus side, the MLM Agreement makes it clear that there is no actual obligation on IMAs to make personal purchases in order to participate so this will come down to how OneLife and its IMAs operate in practice.

The overall numbers of Rookies actively engaged as IMAs and their ability to earn as much as those who purchase the more expensive packages will provide a useful indication of this.

In practice OneCoin operated as an illegal pyramid scheme. Despite Hogan Lovells efforts, there’s no sugar coating it.

6. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: No obligation to purchase stock / inventory that can’t be sold back to the seller

Our understanding of how the OneLife MLM scheme works (which has been confirmed by ONSL) is that IMAs are not required to purchase the Educational Package that they market / advertise.

Instead, IMAs make sales referrals to OneLife which then sells the package to customers.

On this basis, the question of IMAs being left with stock / inventory that they can’t sell back to OneLife should not be an issue that needs to be addressed.

If you want to get technical about it, OneCoin never sold anything. Affiliates and their recruits invested in Ponzi points.

This section of Hogan Lovells’ opinion is therefore meaningless.

7. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: Pricing of the Educational Packages

Another important characteristic of legitimate schemes is whether the goods or services being sold by participants are sold at realistic / accurate prices and are actually worth having.

We noted the following actions:

You should examine what percentage of IMAs / users actually view the tutorial videos and complete the quizzes provided in the Educational Packages.

If the numbers who are doing so are low it would imply that the Educational Packages are simply being purchased to access higher commission percentages / bring in more IMAs which would greatly undermine the claim that the product is worth the price paid.

You should examine what percentage of IMAs / users use the learning, tools and techniques delivered through the Educational Packages to successfully trade and/or otherwise benefit and how they do this.

There should hopefully be good evidence available by now of the benefits derived.

It would also be useful to compare the cost and content of the Educational Packages against similar offerings from accredited educational providers of courses seeking to achieve similar learning outcomes and to be able to demonstrate that similar or better outcomes are being achieved for OneLife Educational Package customers.

ONSL’s partnership with a Chinese University listed in the Top 50 Globally might be a good reference point for this purpose. [Note: As discussed, care will need to be taken to ensure that such an institution is accurately described to IMAs / consumers]

OneCoin had a partnership with a Chinese university? Lulz!

At its peak, OneCoin was bundling PDF files of stolen copypasted content with €250,000 EUR Ponzi points investment.

I don’t think even Hogan Lovells would be able to argue that was “realistic price”.

8. Pyramid Scheme Prohibition: Sale contracts with consumers

There is currently no sale and purchase agreement between OneLife and IMAs or consumers who purchase the educational packages.

Neither the IMA Agreement nor the general Terms covers the terms of these sales. If such agreement does not exist we would strongly advise that one is drafted.

The point here is that there is no sale and purchase agreement between OneLife and purchasers of the Educational Packages who are not IMAs (i.e. who are consumers).

The reason no such agreement exists is because OneCoin affiliate investors recruited OneCoin affiliate investors.

There were no retail sales within the company.

9. Misleading Action Prohibition

OneLife should review and amend the training packages for IMAs as appropriate to ensure that the training IMAs receive is effective and sets out enough information to enable them to conduct business without breaching regulation 5 of the CPRs.

How do you train affiliates to promote a Ponzi scheme?

10. Misleading Omission Prohibition

OneLife should review and amend the training packages for IMAs as appropriate to ensure that the training the IMAs receive is effective and sets out enough information to enable them to conduct business without breaching regulation 6 of the CPRs.

Oh, so you promote a Ponzi scheme by not mentioning it’s a Ponzi scheme. Got it.

11. Aggressive Commercial Practices Prohibition

OneLife should review and amend the training packages for IMAs as appropriate to ensure that the training and information the IMAs receive is effective and sets out enough information to enable them to conduct business without breaching regulation 7 of the CPRs.

I think Ken Labine’s high-pitched squawking on YouTube was about as close to “aggressive marketing” as a I saw within OneCoin.

Not that they ever did anything about it. Labine was even hired to speak at one or two low-key OneCoin events from memory.

12. Commercial practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair

OneLife should have a policy in place and undertake training to instruct IMAs on practices which are prohibited in all circumstances, including examples of the type of activity that would be caught.

Below are the practices that we believe are most relevant with – where appropriate – an example of the type of activity that likely be caught:

(i) “Claiming that a trader (including his commercial practices) or a product has been approved, endorsed or authorised by a public or private body when the trader, the commercial practices or the product have not or making such a claim without complying with the terms of the approval, endorsement or authorisation.”:

This might be triggered if an IMA falsely claimed that that IMA was a member of the DSA (or another public or private body).

(ii) “Making an invitation to purchase products at a specified price without disclosing the existence of any reasonable grounds the trader may have for believing that he will not be able to offer for supply…those products at that price…”:

This practice is self-explanatory.

(iii) “Falsely stating that a product will only be available for a very limited time, or that it will only be available on particular terms for a very limited time in order to elicit an immediate decision…”:

This might be triggered if, during a home visit, an IMA falsely indicated that the Educational Packages were only available for purchase for a very limited time (i.e. that day) in order to generate a sale.

(iv) “Stating or otherwise creating the impression that a product can be legally sold when it cannot.”:

This practice is self-explanatory.

(v) “Presenting rights given to consumers in law as a distinctive feature of the trader’s offer.”:

This might be triggered if an IMA claimed that a 14 day cancellation right was a distinctive product feature that would not be available elsewhere (whereas, in fact, the consumer benefits from this right under statute).

(vi) “Using editorial comment in the media to promote a product where a trader has paid for the promotion without making that clear in the content…”:

This is self-explanatory.

(vii) The Pyramid Scheme Prohibition:

We considered this in detail in the Original Advice.

This pretty much reads like a laundry list of how OneCoin was promoted, by the company itself and its promoters.

(i) OneCoin and its promoters spent years running around falsely claiming authorities in various countries had given them the all-clear.

(ii) OneCoin didn’t sell products, they solicited investment in Ponzi points.

(iii) OneCoin had plenty of “limited time” promotional offers (Chinese New Year anyone?), all for the sole purpose of getting people to invest via a sense of false urgency.

OneCoin’s Ponzi points were recorded on a database, there was never any scarcity or supply issues.

(iv) Ponzi points cannot be legally marketed in the UK or anywhere else in world.

(v) I’m not aware of anyone ever getting a refund in Onecoin. Once you handed over your money that was it.

(vi) What, like Forbes or Financial IT?

(vii) We don’t have the original 2016 Hogan Lovells document so I can’t comment on what pyramid scheme advice they gave to OneCoin.

(viii) Would touting OneCoin’s entirely made up internal Ponzi points value to solicit investment count?

Because that’s exactly what OneCoin corporate did at events. Naturally this was parroted by their investors all over social media.

(ix) Nobody ever got “after sales service” when OneCoin collapsed in January 2017.

(x) Bit of a stretch to believe nobody was ever coerced or pressured into investing into OneCoin.

The number of victims makes it highly unlikely. But this isn’t something I’d expect Hogan Lovells to be able to comment on (in case it wasn’t clear I’m giving them a pass).

(xi) See above.

The rest of Hogan Lovells’ opinion goes on about tweaking the IMA agreement (to protect OneCoin from liability) and is terribly boring, so I’ll leave it there.

Conclusion and Thoughts

Not surprisingly, Hogan and Lovells legal opinion rings hollow.

Not because of the content itself, but because, whether intentionally or otherwise, the law firm fails to address OneCoin’s investment opportunity.

The document does reference OneCoin affiliate’s “trading accounts”, so it seems on some level they were aware of the investment side of the business.

Why that wasn’t pursued I can’t say.

OneCoin’s MLM business was the marketing arm of their fraudulent investment scheme. The two were inseparable and you can’t analyze one without the other.

A Ponzi scheme requires constant recruitment of new investors to survive, and that’s all OneCoin’s MLM operations were a vehicle for.

I maintain that any law firm commissioned by OneCoin for a legal opinion, that didn’t advise them to stop running a Ponzi scheme, was complicit.

The two attorneys Hogan Lovells assigned to OneCoin certainly don’t appear to have any excuse.

Roger is a partner in our Commercial and Retail Banking team, with particular experience in payments, consumer credit and mortgage regulation.

He works with a broad cross-section of banks (both international and local, established and challenger), specialist lenders and payment service providers and infrastructure providers.

As part of our Commercial and Retail Banking team, and with wealth of experience, Oliver Irons advises a broad range of clients on financial law and regulation.

In addition to his experience in private practice, Oliver has spent time on secondment with the Financial Conduct Authority where he worked on the implementation of PSD2 and development of regulatory guidance and at a leading multinational bank focusing on financial regulation and compliance.

An actual legal opinion, even when restricted to UK law and OneCoin’s MLM opportunity, should have taken into consideration what OneCoin was promoting.

In this analysis you can include the promotional packages. But what you can’t do is pretend the investment scheme didn’t exist.

That’s where I draw the line of culpability and it’s on that line that Hogan Lovells evidently chose money over professional integrity.

To be clear, Hogan Lovells is in no way responsible for OneCoin’s multi-billion dollar Ponzi scheme. They had nothing to do with its creation, operation or management.

What they did do is fail to accurately analyze the business.

When Tym and Irons came up short, they evidently didn’t push OneCoin for answers and instead tiptoed around discrepancies.

Informing Ruja Ignatova there was simply no way to run OneCoin legally might have cost Hogan Lovells future business, but at least it’d have been the truth.

I am not a lawyer, so take this for what it’s worth. Because I was a bit confused by some of the terminology used here, I did some googling, and I think I might be able to clarify a bit.

The “Pyramid Scheme Prohibition”, and the other “Prohibitions” they keep referrring to aren’t, despite what the capitals might suggest, phrases directly taken from any law. They are descriptions of the overall result of various legal provisions.

The “UK’s Unfair Commercial Practices Directive law (UCPD)” doesn’t exist under that name. There is an EU Directive, the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (2005). Directives are commonly referred to as “EU laws”, but each member state (which the UK still was at the time) must implement these in their own legislation.

In the UK’s case, that was done not through an Act of Parliament but through a Statutory Instrument (that’s just another kind of law), resulting in the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008.

Because that’s a straighforward implementation of the EU directive, it is commonly referred to as the UCPD, even though that abbreviation doesn’t match its actual UK title. To confuse things a bit more, Hogan Lovells also refer to the same law as “the CPRs”.

The only direct mention of pyramid schemes is in Annex I of the EU Directive, which appears in nearly verbatim form in the UK law, but titled Schedule 1.

It contains a list of “Commercial practices which are in all circumstances considered unfair” (everything quoted under 12 above is from that Annex/Schedule), and one of these is:

There are obviously a lot of other factors not mentioned in that one short paragraph that would go into a court’s assessment of whether or not something is a pyramid scheme (including lots of case law, much more important in the UK than elsewhere in Europe), and Hogan Lovells jointly refer to all of that as the Pyramid Scheme Prohibition.

Schneider or Ricketts? And why did Ruja need to be told this? Was she not in control?

Was this reported by the authorities as per H-L’s statutory obligations? Who saw that report? Is it the same addressees as listed here?

I can’t answer both questions.

The conclusion that Hogan Lovells’ 2016 report found OneCoin to be a pyramid scheme is based on them issuing “certain areas that required further consideration”.

If OneCoin wasn’t a pyramid scheme there’d have been nothing to address.

IMHO, HL ONLY addressed what they were handed, i.e. the MLM model. The weren’t paid to do a full investigation on OneCoin, so they didn’t. Tip of the iceberg and all that.

The MLM model revolved around convincing people to invest.

You gonna tell me these lawyers didn’t stop and wonder why people were dropping 250,000 EUR on PDF files filled with stolen content?

They had the access and chose to turn a blind eye to the crucial stuff.

I would love to here Gary G doing the,

-its impossible i tell you, impossible to know onecoin was a scam, since i don`t know what the internet is used for, and i dont read emails, and

-ruja didnt stright up tell me its a scam, now go buy me a house whit my scam monies , oh and have some for your troubles.

I find this article rather simplistic and biased. The document in question is a legal opinion that was ordered to assess MLM activities and it’s criticised for being just that.

On what grounds is the law firm supposed to have advised their client to “stop running a Ponzi scheme”?

You work at a law firm. One day this portly woman with a funny accent walks in the door and hands you a boatload of money.

“I want you to tell me if my company is a pyramid scheme”.

You begin researching the company and request information as you require it. You soon discover people are paying up to 250,000 euros for education packages.

This strikes you as odd.

You have two options at this point:

A. You swallow your curiosity (read: turn a blind eye) and put together a legal opinion that dances around the glaringly obvious; or

B. You ask for more information to get a clearer picture of the business. You realize, because you’re supposedly an expert in financial regulation, what you’re dealing with and put together a report.

In your report you advise your client that committing multi-billion dollar investment fraud isn’t going to end well.

What your client does with your report is up to them. You want nothing more to do with them so you terminate your professional relationship.

We saw this happen with companies like Apex when it came to Mark Scott’s money laundering network.

OneCoin’s MLM activities are an intrinsic component of the Ponzi scheme. Anyone who pretended otherwise needs to be held accountable.

I’m certainly not a lawyer, yet armed with nothing but OneCoin’s business model was able to identify a Ponzi scheme back in 2014.

You want to tell me these expert lawyers who were likely paid ungodly sums didn’t know what was up? Please.

And lets not forget, No other streams of revenue other then the Ponzi/pyramidscheming was found our could be identified (obvoius just by reading the compplan)

No doubt “lawyers” have to shear bunkbeds whit rapists and pedhopiles in hell…

“Robert” – Courtneidge… How dare you weigh in?

It is time you pulled your bald head out from somewhere between your legs.

While you might think it smart to blur the lines and offer your own worthless opinion, four billion is missing and lives are ruined.

You were part of this and we all look forward to your comeuppance with ePayments and what the relationship with Ruja was exactly.

Your name is all over the documents from the NY trial, you worked with Mark Scott FFS. You glowed over OneCoin (and I dare you to deny it).

I’m sorry if the article is “biased” against one of the top earning law firms overlooking a scam when they had a duty to report it and do a proper job.

You are part of the problem. We don’t care what you think. We care what the US courts are going to rule.

You and your happy band of the likes of H-L, Chelgate, Carter Ruck, Sandstone, LockLorde, ePayments, etc, are getting what you deserve.

Documents are leaking so fast that there is nothing you nor your smugness can do to stop you from soon appearing in NY.

Via email:

What small (and shady, and incompetent) circles these people live in. Because Chelgate leads us right back to Frank Schneider.

One of the other known dubious clients of Chelgate (although given the nature of their business, really all their clients are dubious) is the Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, who hired them when he began getting into trouble over the murder of the journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

The very respectable online publication EUObserver reported on this (//euobserver.com/justice/146821):

The sheer incompetence shown by those last two paragraphs had me laughing very hard. Frank Schneider, master spy. Oh dear. No wonder he’s too dumb to be able to check whether a Chinese university “listed in the Top 50 Globally” exists or not.

Schneider, BTW, keeps on denying he had anything to do with the report described. He also claims the following (Dec. 2019):

Except for this claim in a press release from Sandstone, nearly four months ago, I can find no evidence that any such legal proceedings actually exist. EUObserver hasn’t written anything about it as far as I can see, which would be quite unusual for any publication being sued.

It’s also very strange that that press release put out by Sandstone denies several things that only Chelgate can know about.

How can Schneider possibly know who, besides Sandstone, Chelgate has dealings with, unless they’re de facto the same company?

The claim about ongoing criminal proceedings in Luxembourg is particularly strange:

(a) A private individual or company obviously cannot launch criminal proceedings. How would Schneider know they’re ongoing, since there has been no announcement about any such thing from any Luxembourg official?

As long as it’s not been publicly acknowledged, law enforcement agencies don’t go around telling private individuals about investigations, so they can then trumpet it around in press releases. Especially not people of ill repute like Schneider.

(b) Even if what EUObserver wrote wasn’t correct, what about it could possibly amount to a criminal offence, in any EU country, or merit any attention from the authorities?

He admits that the bogus report referred to exists, and that Sandstone had a copy. He just denies they wrote it, or gave it to Chelgate. A news outlet getting a fact like that wrong is not a crime, anywhere.

(c) EUObserver is incorporated, and its editorial offices are located, in Belgium. What jurisdiction does he think the Luxembourg courts have over them? (Possibly, he is aware that criminal prosecutions of an organ of the press are as good as impossible in Belgium, which would make his grandstanding sound even more ridiculous.)

@PassingBy

I think Frank Schneider’s Muscat-operation with Chelgate bears some resemblance with the Cargolux affair he was involved in over ten years ago.

As an intelligence official, he wrote a report full of “exotic theories” in hopes of engineering a beneficial outcome for his favoured parties tied to Cargolux:

(machine translate from: forum.lu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/7579_327_GoebbelsFranck.pdf)

Even back then many saw Frank as an untrustworthy crook, and weren’t fooled by his schemes.

It appears that one of Frank’s services — in addition to helping elite criminals like Ruja launder money and evade law enforcement — is to lend his helping hand to conduct information — or “PR” — operations beneficial to these high-level crooks.

Frank invents manipulative falsehoods that aid his customer, puts the fabrications into his shoddy “intelligence reports”, and then his lies get rubber-stamped by Chelgate (or some other “prestigious” entity) and weaponized in information/PR operations. (It’s an “infromation laundering” scheme of sorts.)

yeah it seems easy to say lawyers didn’t do their job well, but lawyers do what they are told within the confines of the information of what they are given.

Did it occur to you that perhaps onecoin didn’t provide any incendiary information to lawyers, and so the lawyers worked with what they got.

Am not a lawyer, but I have worked with quite a few and they work within the information you give them, and likely onecoin since it is their habit to hide information, they did the same with the lawyers to try to get a response they could live with. note to all analyzing things: use an analytical mind.

I don’t publish a review unless I can obtain a copy of a company’s compensation plan.

Similarly, law firms should not be putting together pyramid scheme legal opinions without consideration of an MLM company’s compensation plan.

And it’s not like any of this was secret, Hogan Lovell could have just visited OneCoin’s website to see what people were investing in and how they were paid.

Even with access above and beyond that to OneCoin corporate, they chose to publish a report that dances around the obvious.

Shoddy lawyering because money. That’s all this is.

Oz, what exactly are you criticising here? That the law firm didn’t find Onecoin to be a pyramid scheme?

I’m confused now because your article above says there was a 2016 legal opinion that did find “that Hogan Lovells found OneCoin was a pyramid scheme, as per UK law.”

@Ebenezer. Lol. I don’t think I’m the Robert you’re looking for.

Hogan Lovell’s 2016 legal opinion, based on its reference in the 2017 report, made recommendations to counter OneCoin being a pyramid scheme.

These weren’t acted on or were superfluous, because OneCoin never implemented retail.

The 2017 legal opinion turns a blind eye to fraud, which the 2016 opinion, again based on how it is referenced, didn’t.

Links to both Hogan Lovells’ Memorandums are here:

docdroid.net/tVh72lb/hogan-lovells-onecoin-memorandum-november-25-2016-pdf

docdroid.net/BGO1yjK/hogan-lovells-onecoin-memorandum-march-30-2017-pdf